One story stood out from the rest this week@work. Washington Post journalists Emily Badger and Christopher Ingraham reported on the findings of sociologist Mark Rand at Washington University. The title alone was attention grabbing: ‘The remarkably high odds you’ll be poor at some point in your life’.

“The poor in America are not a permanent class of people. Who’s poor in any given year is different from who’s poor a few years later.

By the time they’re 60 years old, Rank has found, nearly four in five people experience some kind of economic hardship: They’ve gone through a spell of unemployment, or spent time relying on a government program for the poor like food stamps, or lived at least one year in poverty or very close to it.

By age 60, nearly 80 percent of us will have gone through a rough stretch.

“Rather than an uncommon event,” Rank says, “poverty was much more common than many people had assumed once you looked over a long period of time.”

The age of job stability is over, if anyone was still hanging on to an ideal of job security. Financial planning is a critical component of long term career planning. The reality of the research is that there will be periods of economic challenge alternating with periods of affluence. The ‘poor’ are not some abstract population. They are your neighbors, family and friends.

A story in The New York Times offered an example of how attitudes toward work and career might alter a family’s income. Journalist Claire Cain Miller writing for the Upshot found that the most recent entrants to the workplace envision planned pauses in their careers.

“The youngest generation of women in the work force — the millennials, age 18 to early 30s — is defining career success differently and less linearly than previous generations of women. A variety of survey data shows that educated, working young women are more likely than those before them to expect their career and family priorities to shift over time.

The surveys highlighted that two generations after women entered the business world in large numbers, it can still be hard for women to work. Even those with the highest career ambitions are more likely than their predecessors to plan to scale back at work at certain times or to seek out flexible jobs.

You might call them the planning generation: Their approach is less all or nothing — climb the career ladder or stay home with children — and more give and take.”

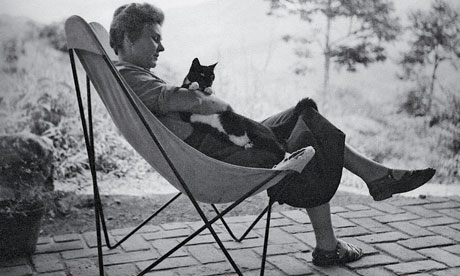

Recalling the career of journalist Marlene Sanders who died last week, Katherine Rosman shared the story of a member of the generation who achieved professional distinction while being among the first to ‘work outside the home’.

“In 2000, Cynthia McFadden, the senior legal and investigative correspondent for NBC News, attended a party given by her friend Jeffrey Toobin, a staff writer for The New Yorker and legal analyst for CNN. There, Ms. McFadden was catching up with Mr. Toobin’s mother, Marlene Sanders, the pioneering television reporter. She asked for her advice on managing motherhood and a career.

Ms. Sanders put both hands on Ms. McFadden’s shoulders and peered into her eyes. “Never apologize for working,” the older woman said. “You love what you do, and loving what you do is a great gift to give your child.”

Over the years, Ms. McFadden said, Mr. Toobin told her he loved having a mother who worked outside the home, even in an era when it was not that common. It was a sentiment he reiterated in an interview on Wednesday. “I found her career exciting,” he said. “I loved to watch her on TV. Guilt was never part of the equation. And given her temperament, if she had been home all the time, it would have been a close contest to determine whether she or I went insane first.”

The last story of the week shares research that should encourage you to take a walk in the park. Reporting on a study at Stanford University, Gretchen Reynolds found:

A walk in the park may soothe the mind and, in the process, change the workings of our brains in ways that improve our mental health, according to an interesting new study of the physical effects on the brain of visiting nature.

But just how a visit to a park or other green space might alter mood has been unclear. Does experiencing nature actually change our brains in some way that affects our emotional health?

That possibility intrigued Gregory Bratman, a graduate student at the Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources at Stanford University, who has been studying the psychological effects of urban living. In an earlier study published last month, he and his colleagues found that volunteers who walked briefly through a lush, green portion of the Stanford campus were more attentive and happier afterward than volunteers who strolled for the same amount of time near heavy traffic.”

In summary this week@work – take a walk in the park and consider your career path. Lose the guilt if you are a working mother, and plan for both the expected as well as the unexpected shifts in work/life balance.