One summer I worked in the restaurant at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. No, not one of those that exist today, but the Dorothy Draper designed open space with water, and muses, and gigantic lighting fixtures; furnished with wrought iron tables and chairs and situated at the south end of the building, in the Lamont Wing’s Roman courtyard. The enormity of the space required a hostess (me) to direct hungry museum-goers further south to a self-service cafeteria area. Once seated, waiters would bring beverages and clear the remains of lunch.

We were members of ‘support staff’, contract labor, adjunct to the mission of The Met. But what a collection of unique experience and talent was hidden from view, behind the facade of a job description!

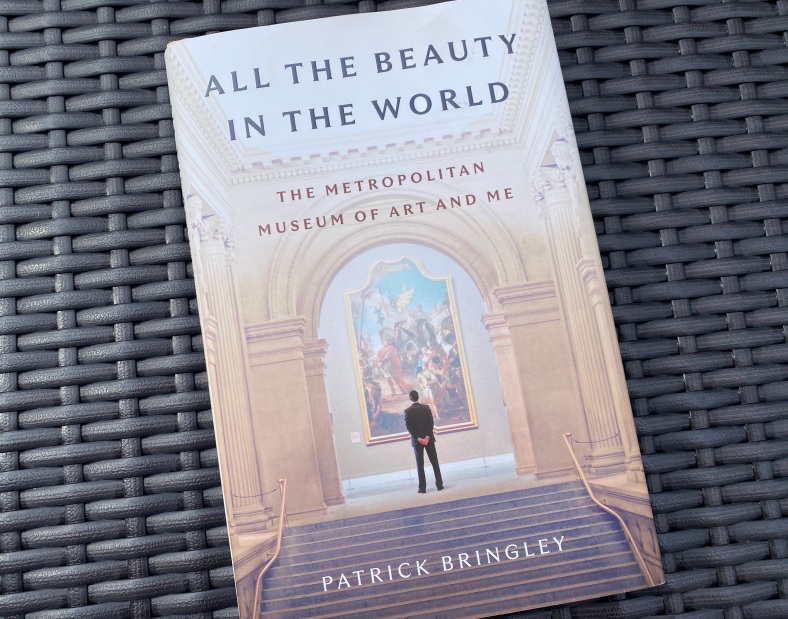

It was the memory of that New York summer that drew me to Patrick Bringley’s new memoir, ‘All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me’. Change is a constant and so is beauty. Exhibits rotate, curators create new visual displays, and the museum for the most part, remains blind to the resumes of life experience serving within its marble walls.

Bringley changes the script a bit by sharing his own experience while introducing the reader to some of his colleagues in dark blue suits – keeping the art safe by day, engaging in their individual creative outlets once they leave the building.

We’re all more than our job description. Some folks will never get that. Patrick did.

In the fall of 2008, Patrick Bringley added ‘museum guard’ to his resume, after a stint at The New Yorker “… in a small, somewhat glamourous department that produced the magazine’s public events…”

Like many recent college grads, “… more than a bit blinded by the bright lights…”, he anticipated great success within the culture of an iconic institution. “But it’s very hard, when you’re in a good light – “where did you say you work? The New Yorker?!” – to accept that it isn’t you: it’s just light.”

It’s the insight we get when we take time to reflect on those first career choices:

“I don’t know exactly what I expected upon entering “the real world” after college, but I expected that it would feel real.”

Life events intervene. “I applied for the most straight-forward job I could think of in the most beautiful place I knew. This time I arrive at the Met with no thought of moving forward.”

The book is a workplace memoir, a meditation on beauty and an insider’s tour of one of the world’s most famous places.

It’s a personal reflection on career, identity and finding community where you may least expect it. For me, this book is a recognition that each career choice is an overlay of the one before, fitting for the moment. “Not so long ago, I had a very different sort of job, one where they told me I was “going places” … I find myself happy to be going nowhere.”

And it’s a book about working in a place of beauty. “I have spent my hours absorbing art, but what if instead I actively wrestle with it, trying to bring all different aspects of myself to bear on the questions it raises? It seems to me that this is a worthy mission for anybody entering an art museum. After we quiet our thinking mind to experience art, we will want to switch it back on, reassert ourselves, and in that way learn even more.”

After a decade at the museum, it’s time for a new career choice. “I don’t have a simple purpose anymore, as I did when I came to the museum. Instead I have a life to lead.”

Lucky for the reader, one of his choices was to write his memoir.

And, about that ‘water feature’ in the middle of the restaurant in the Lamont Wing… the muses are now out of the darkness, in the sunshine.

“At the center of the pool was a work commissioned by the Museum from the Swedish-born sculptor Carl Milles, titled The Fountain of the Muses, which now resides with Brookgreen Gardens—a sculpture garden and wildlife preserve located in Murrells Inlet, South Carolina.”