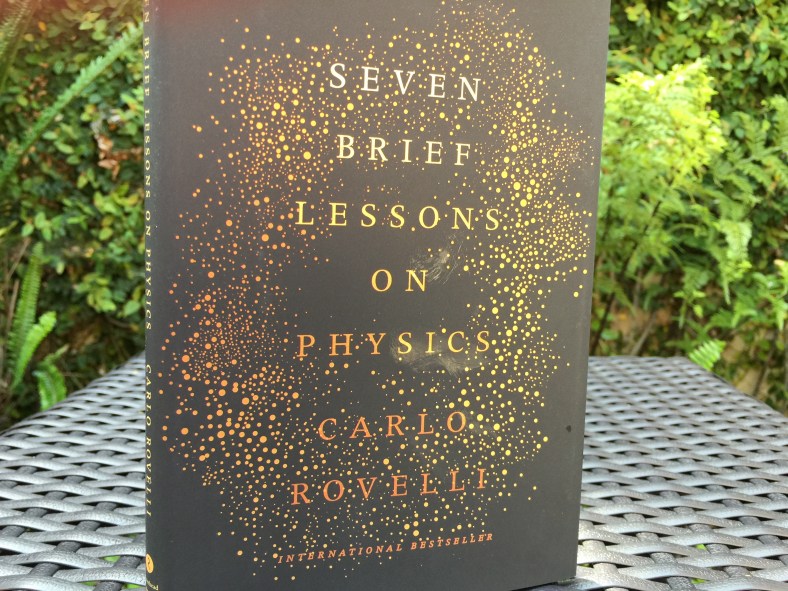

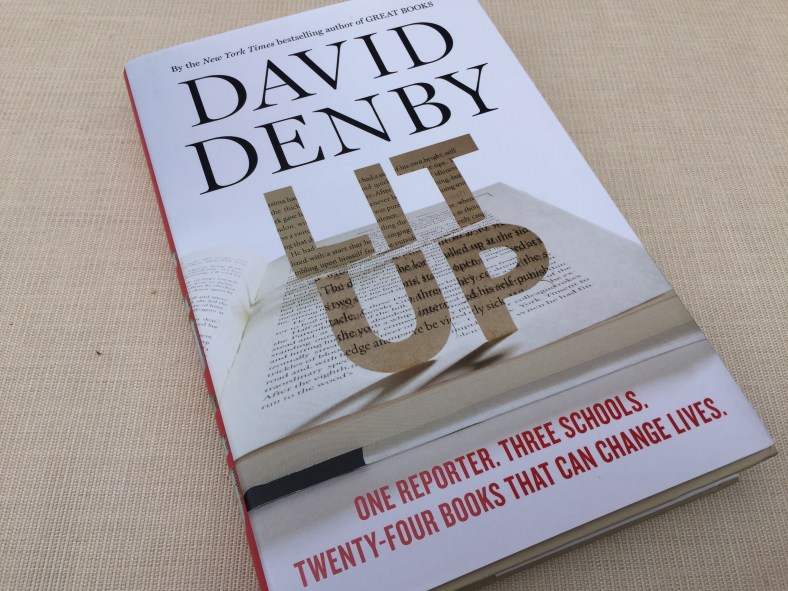

If you believe that the humanities are as critical as STEM skills in the 21st century workplace, take a trip back to high school with David Denby and this week’s Saturday Read, ‘LIT UP’: One Reporter. Three Schools. Twenty-Four Books That Can Change Lives.

We have this basic disconnect in our workplace today that is pitting generalists against specialists. The consequences are trickling down into our public education system.

If you’re a parent considering where to invest in your child’s college education, you’re probably looking at ‘vocational’ programs that ‘guarantee’ a job at graduation. If you’re that same parent, but now in the role of organization executive, you realize your recruiting efforts must consider ‘cultural contribution’; potential in addition to skill set. If you’re a student, you hear ‘STEM good, humanities bad; or worse, a waste of time’.

Writing in The New Yorker in February, Mr. Denby addressed the challenge in advocating for the humanities in today’s skill driven education/employer complex. He cited recent state government efforts to offer ‘bonus premiums’ in financial aid to students enrolled in STEM degree programs by cutting funding to students in the humanities.

“Lifetime readers know that reading literature can be transformative, but they can’t prove it. If they tried, they would have to buck the metric prejudice, the American notion that assertions unsupported with statistics are virtually meaningless. What they know about literature and its effects is literally and spiritually immeasurable. They would have to buck common marketplace wisdom, too: in an economy demanding “skill sets”—defined narrowly as technical and business skills—that deep-reading stuff won’t get you anywhere.”

In ‘LIT UP’ David Denby is searching for the magic that transforms a young reader into a lifetime reader. “How do you establish reading pleasure in busy screen-loving teenagers – and in particular, pleasure in reading serious work? Is it still possible to raise teenagers who can’t live without reading something good? Or is that idea absurd? And could the struggle to create such hunger have any effect on the character of boys and girls?”

He chooses to go back to school for the 2011-12 academic year at Beacon, a New York City magnet high school, at the time located on West 61st St, observing teacher Sean Leon‘s tenth grade English class.

“School was the place to find out. And students in the tenth grade, I thought, were the right kids to look at. Recent work by neuroscientists has established that adolescence, as well as early childhood, is a period of tremendous “neuroplasticity”. At that age, the brain still has a genuine capacity to change.”

The book is structured by months, and reading selections. Mr. Leon introduces each book with inventive assignments, questions and at one point, a ‘digital fast’. Mr. Denby provides thumbnail plot sketches to shake the cobwebs from our ‘required reading’ memories. And we meet the students, by pseudonym, in their reactions to the literature.

At one point, the author gives the students a questionnaire to find out what books they read on their own, and their favorite authors. He finds three ‘real readers’ in a class of 32. “…unfairly or not, I was sorry that among Mr. Leon’s students there were no mad enthusiasms, no crazy loves, no compulsive reading of every book by a single author…”

In writing the book, he was encouraged by colleagues to create a scalable review, contrary to his initial approach, resisting quantification, and observing “a single place where literary education seemed to be working.”

He realized that you can’t clone Beacon’s Sean Leon. He wanted other teachers to learn from Leon’s methods, but realized additional perspectives would add to his narrative.

“Typicality and comprehensiveness remained impossible to achieve, but variety was not. I delayed finishing the book, and, in the academic year 2013-14, I visited tenth-grade English classes in two other public schools – shuttling up many times during the year to James Hillhouse High School, an inner-city school in New Haven with a largely poor African American population; and five times in the spring to a school in a wealthy New York suburb, Mamaroneck, a “bedroom town” in the language of the fifties, where people sent their kids to good schools.”

Mr. Denby’s appendix includes the reading lists for each of the schools he visited and a ‘where are they now?’ college destination roster of the Beacon English Class of 2014. “There is, of course, no ideal reading list, no perfect syllabus, no perfect classroom manner, but only strategies that work or don’t work. In a reading crisis, we are pragmatists as well as idealists.”

“Teenagers, distracted, busy, self-obsessed, are not easy to engage – not by their teachers or by their parents. To keep them in the game, the teachers I watched experimented, altered the routine, changing the physical dimensions of the class. They kept the kids off balance in order to put them back in balance. They demanded more of students than the students expected to give.”

This is a book for parents, parents who are business leaders; teachers and the politicians who minimize their value; and students. We’re in a reading crisis and we need folks who have emotional intelligence, who can think, judge, make decisions and create a vision for an enterprise within a global world view.

“Teachers are the most maligned and ignored professionals in American life. In the humanities, the good ones are as central to our emotional and moral life as priests, ministers, rabbis, and imams. The good ones are not sheepish or silent in defense of literature and history and the rest. They can’t be; the children’s lives are right before them. In high-school English, if the teachers are shrewd and willing to take a few risks, they will try to reach the students where they live emotionally. They will engage, for instance, with “naïve” existential questions (what do I live for?) and also adolescent fascination with “dark” moods and the fear of being engulfed by adult society. Shakespeare, Mary Shelley, Poe, Hawthorne, Twain, Stevenson, Orwell, Vonnegut, and many others wrote about such things. And if teachers can make books important to kids—and forge the necessary link to pleasure and need—those kids may turn off the screens. At least for a few vital hours.”

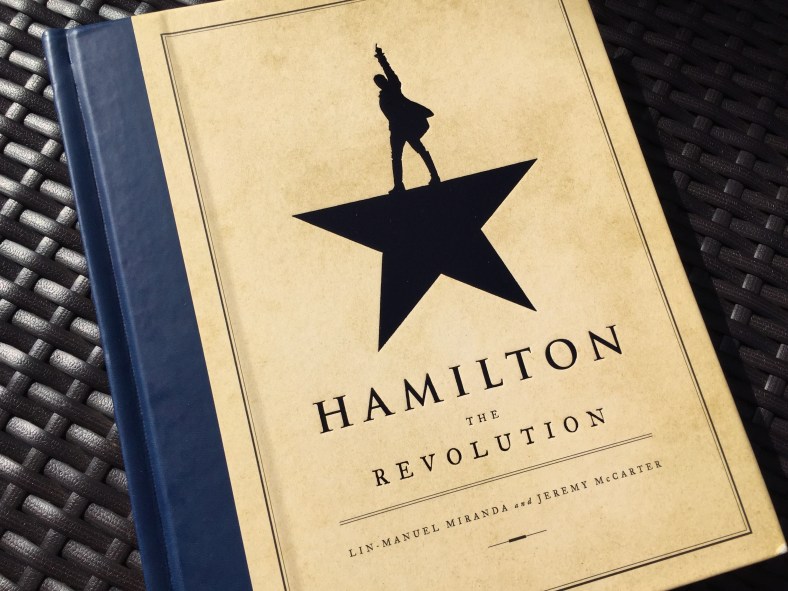

The book is a ‘behind the scenes’ look at the development of a musical. It’s a narrative of the creative process and a roadmap for future generations who will replicate the production on high school and summer stages.

The book is a ‘behind the scenes’ look at the development of a musical. It’s a narrative of the creative process and a roadmap for future generations who will replicate the production on high school and summer stages. We learn from the wisdom of others. ‘Hamilton The Revolution’ introduces us to a serious set of theater luminaries and traces each of their stories as the words and music evolve.

We learn from the wisdom of others. ‘Hamilton The Revolution’ introduces us to a serious set of theater luminaries and traces each of their stories as the words and music evolve.